Table of Contents

Family tension is a normal part of life, but for children, it can be confusing and distressing. Whether they witness a loud argument, feel caught in a parenting conflict, experience intense sibling rivalry, or hear about these through stories, films, or peers, kids are directly and indirectly exposed to the emotional undercurrents of the home environment.

This article explains why it’s important to talk about family issues with children, why schools may not be the best place for these discussions, and how parents can approach these conversations in age-appropriate, emotionally healthy ways.

Why Discussing Family Tension with Children Matters

Children don’t just learn by instruction, they learn by observation. In early development, they’re constantly absorbing emotional cues and forming beliefs about what is acceptable behaviour in relationships. Kids often copy how adults handle big emotions like frustration or anger. If a child regularly sees adults yelling, ignoring, or blaming, they may believe these are normal ways to resolve family tension or conflict. Without guidance, children may start to internalise unhealthy dynamics as acceptable. Over time, this can lead to poor emotional regulation, damaged relationships, and difficulties in their own parenting or adult life. By openly discussing family conflict, parents help children:

- Develop emotional literacy

- Learn conflict resolution skills

- Understand that making mistakes is human, and repair is possible

Should Teachers Teach Children About Family Conflict?

Classrooms are often described as safe and learning spaces, but when it comes to highly sensitive topics such as family issues, they are not always the most appropriate setting for explicit teaching, particularly in primary schools.

- Professional policies: According to child protection guidelines in most Australian states, teachers may need to protectively interrupt a child who begins disclosing inappropriate personal information in front of peers. This may include, but is not limited to, distressing family experiences. The strategy is used to redirect the conversation and provide the student with an opportunity to speak in a safe and confidential setting. Lessons on recognising emotions, calming strategies, or resolving conflict with peers are appropriate and fall within the curriculum scope, but explicit discussions about family tension do not.

- Emotional safety for all students: A conversation about parent-to-parent or parent-child conflict may hit too close to home for some children and be inappropriate for others. Children who haven’t experienced family conflict may become confused or worried, while those from high-conflict homes may feel overwhelmed or triggered. Classrooms must remain emotionally safe for all students. Sensitive topics should be handled supportively but privately and appropriately.

- Trust-based settings: Home is often the best environment to explore this topic with gentle, age-appropriate guidance. A trusted adult, like a parent or carer, can offer reassurance and context while tailoring the conversation to the child’s emotional readiness.

How to Start a Conversation About Family Tension

Conversations about family tension or its resolution don’t have to be heavy or dramatic. based on the child’s readiness and openness, parents can begin gently with emotional awareness and gradually exploring respectful ways to handle conflict for both adults and children.

Understand Big Emotions Like Anger

Anger is a natural emotion that arises when things don’t go as expected. Both adults and children struggle with it at times. When unmanaged, anger can explode into yelling, blaming, or silence. Even we, the adults, are still learning to manage them. Help children explore what anger does to our bodies and minds, and the negative impact it can have on our health and relationships. This helps them understand that tension within families or among peers often comes from losing self-control, not from being a “bad” person.

Questions to explore together:

- What does our body feel like when we’re really angry? Can you think of any other feelings besides anger that might be hiding underneath?

- Have you ever felt like you might burst?

- Why do you think people yell sometimes, even if they don’t want to hurt someone?

Activities to explore big emotions:

Repair After Conflict

Once children understand what’s behind a conflict, we can explore how to repair it. The key is to keep ideas simple, relatable, and action-based. Children don’t need complex explanations. They need clear, practical tools they can observe, practise, and grow into.

Here are some age-appropriate ways both parents and kids can repair after a conflict:

- Saying Sorry, and Meaning It: A real apology isn’t just saying “sorry” and walking away. Help kids understand it means acknowledging what wasn’t kind, showing they understand how the other person felt, and thinking about what to do better next time.

- Alone Time: Let kids know it’s okay to take a break when emotions are too big. It’s often better to pause and come back when everyone feels calmer, then return and talk gently.

- Debrief with Honesty: After calming down, talk gently about what happened. Encourage honesty and accountability without blame. This builds trust and shows it’s okay to make mistakes as long as we’re willing to repair them. We might say: “I was really angry and didn’t handle it well,” or “Let’s talk about what we could both do better.”

- Talking It Through Respectfully: Use kind words and “I” statements when expressing feelings, such as “I felt hurt when you…” or “I didn’t like it when…” This builds empathy, listening skills, and respectful communication.

- Making It Right: Sometimes small actions help repair a hurt. Encourage kind gestures like doing something thoughtful to reconnect, helping the other person, or drawing a picture or writing a sorry note.

Questions to explore together:

- Should we say sorry to someone if we yell at them?

- What happens if we say “sorry” quickly and then walk away?

- Is it a good idea to talk to the other person about what just happened?

- When will be a good time to talk to the other person about the conflict?

Prevent Future Conflict

Emotional regulation is a lifelong skill, and it starts with us, the adults. We all need to practise, practise, and practise. There are safe and respectful ways to prevent tension from escalating at home.

Model:

- Deep breathing or calming rituals

- Taking a break before talking when emotions run high

- Discussing sensitive topics respectfully in a private and safe space, for ourselves and for others

Local parenting groups, school psychologists, or family counsellors can also provide support if conflict becomes more serious or repetitive.

Questions to explore together:

- What can we do as a family when things start to feel too much?

- Is there a better way, place, or time for us to talk about hard things?

- Who can we ask for help when we feel stuck in a family problem?

Activities to explore emotional regulation:

Explore through Children’s Books

Using children’s books that illustrate age-appropriate conflict scenes offers a safe and indirect way to help children understand what anger looks like, feels like, and how it affects our bodies and relationships.

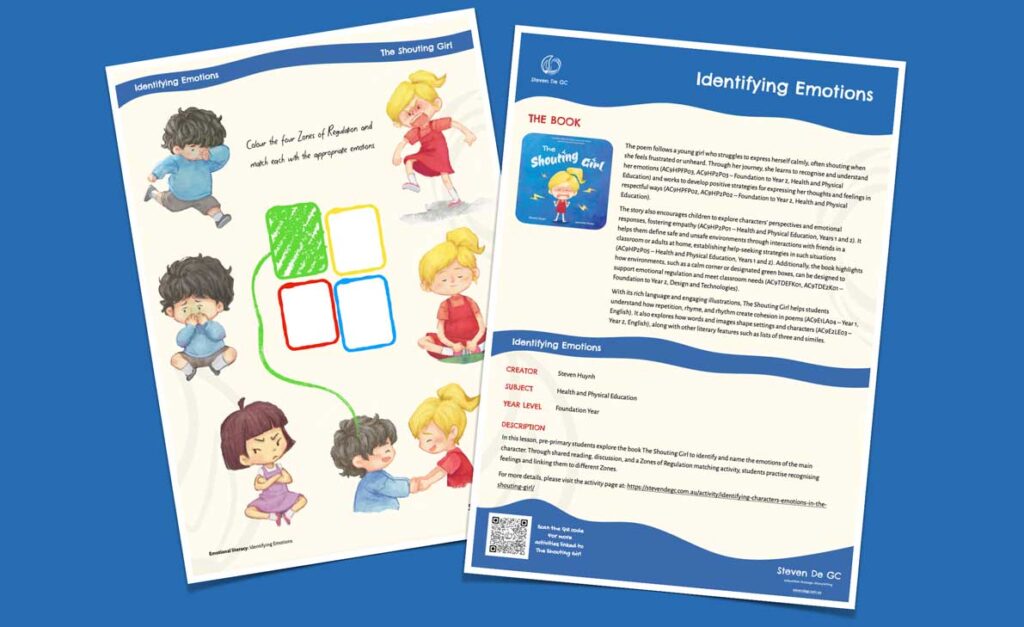

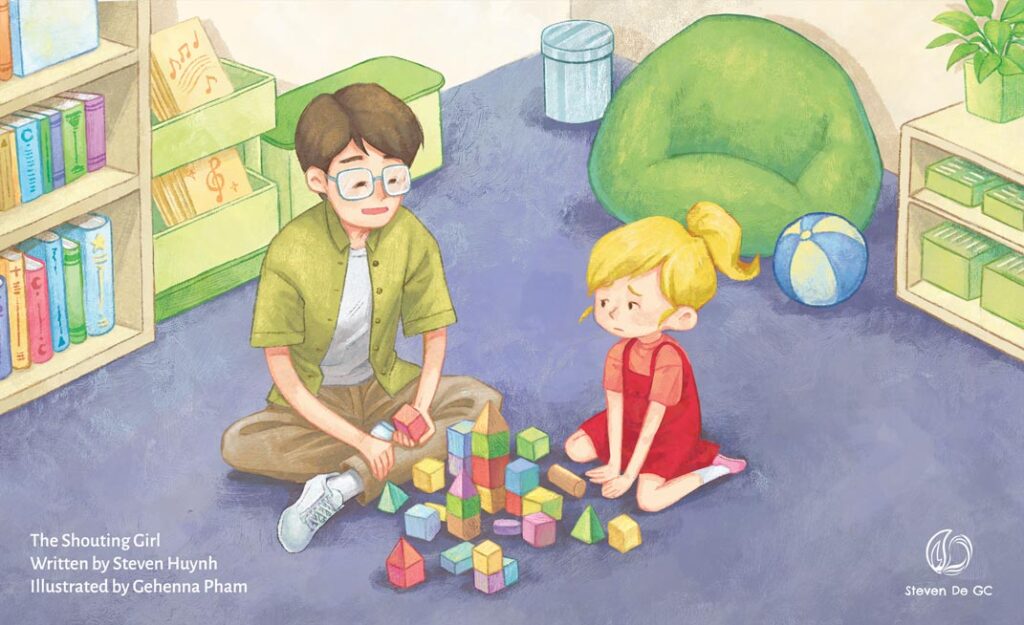

The Shouting Girl by Steven Huynh vividly captures how a child’s experience of family conflict can influence her behaviour with classmates at school. The story subtly illustrates the underlying connection between home and school life, showing how the child mirrors the emotional regulation, or lack of it, she observes in the adults around her. These big emotional outbursts can carry over and affect relationships with both family and peers. The book opens up gentle, honest conversations about big emotions and their consequences from a child’s perspective, and encourages parents and children to explore kinder, healthier ways to express feelings and repair conflict.

Final Thoughts

How can we raise kids who don’t fear disagreement but know how to have healthy conflict and repair relationships? The answer lies not in hiding tension but in guiding children through it gently, openly, and age-appropriately. Whether it’s a sibling conflict, a parenting disagreement, or emotional outbursts, each situation is an opportunity to build our children’s understanding of conflict resolution, empathy, and emotional safety. With ongoing conversations and compassionate modelling, parents can raise emotionally aware, resilient kids, even when family life isn’t perfect.

Leave a Reply